Submitted by Richard J. Holden, PhD

A couple years ago, my Indiana University colleague Shannon Risacher, PhD made national news with a study in JAMA Neurology. Of the more alarming news headlines was one titled, “OTC Meds Shrink the Brain.” Indeed, her study showed older adults taking medications with “anticholinergic effects” had smaller brain volume and worse cognitive function, compared to those not taking these medications.

What are anticholinergic medications?

I first learned the term “anticholinergic” from my collaborators, who are world leaders in studying these medications. (Thereafter, I began seeing these medications everywhere I looked!)

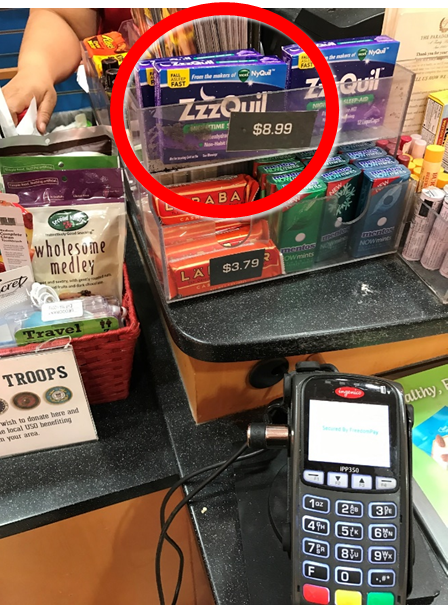

Photo of one of many over-the-counter

products

with anticholinergic effects (circled), taken at

an airport convenience store.

The term “anticholinergic” sounds like something from a $2000 Jeopardy question and we believe few people know the term or what it means, even among those who regularly use anticholinergics. This is partly because the term “anticholinergic” is not found on medication packages or prescriptions. Anticholinergic is not an ingredient; instead, it refers to various ingredients that affect the cholinergic system by blocking acetylcholine receptor sites, thus disrupting the neurochemical process behind human cognition.) Anticholinergics include prescription products such as paroxetine (e.g., Paxil) and oxybutynin (e.g., Ditropan), as well as nonprescription products such as diphenhydramine (e.g., Benadryl) and doxylamine (e.g., Unisom).

Don’t panic!

Headlines about shrinking brains can be frightening, so keep in mind the following. First, all medications have risks and benefits, not just those with anticholinergic effects. Taking any medication should be a deliberate, informed choice, weighing symptom relief against the potential for harm. Second, taking a single dose for seasonal allergies will not vaporize the temporal lobe cortex (although it might make you sleepier the next morning, the so-called “Benadryl hangover”). The effects on the brain appear to be cumulative and related to long-term exposure. Third, findings of harm from anticholinergic medications have come from studies of older adults only. Anticholinergics are on the Beers list of medications that are potentially inappropriate for older adults, but it is not clear whether younger adults are also at risk. Fourth, the studies linking long-term anticholinergic use to outcomes such as dementia, memory problems, and delirium are correlational. Scientists have not yet shown a causal link between anticholinergic medication use and subsequent cognitive changes.

New research on anticholinergic medications

That brings me to another story that was in the national press a couple months ago with equally shocking headlines, like “Commonly prescribed drugs are tied to nearly 50% higher dementia risk in older adults, study says.” That CNN reports quotes from an invited JAMA Internal Medicine commentary I wrote with colleagues Noll Campbell, PharmD, and Malaz Boustani, MD. The two main messages from the commentary are:

- We need studies to test causality between anticholinergics and dementia. There is considerable evidence correlating use of anticholinergic medications with brain harm. But correlation is not causation. Showing causality requires a study in which anticholinergic medications are started or stopped, followed by measures of subsequent cognitive function. (It would be unethical to make people start taking anticholinergic medications, but one can study what happens when they stop.)

As a matter of fact, we just received a total of $6.8 million from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to conduct two such studies: one led by Dr. Campbell, the other by me. In both, we will measure what happens when older adults stop versus continue using anticholinergic medications. - We need anticholinergic deprescribing interventions. The second point of the commentary is the need to develop and test effective interventions to reduce the use of anticholinergic medications. Both newly funded studies will test interventions to “deprescribe” anticholinergic medications.

Deprescribing anticholinergics

For years we have been working on anticholinergic deprescribing. (The term deprescribe means removing or replacing medications a person is taking.) Among our team’s initiatives to help people attain a safer medication regimen, one of the more promising is a direct-to-consumer mobile app called Brain Buddy. The app targets consumers because we have found people taking anticholinergic medications are not aware of their risks. Once they learn of the risks, many want to know what to do next. Brain Buddy is meant to help them take the next step. We recently tested Brain Buddy to see if it is usable and feasible. It is! Brain Buddy received high marks for usability and 100% of our participants felt more informed about their medication safety after using the app. Over 80% also ended up talking to their physicians about their current anticholinergic medications.

Empowering patients and other consumers

We are not the only ones using apps to inform and empower people – or more low-tech approaches to deprescribe medications unsafe for older adults. However, our app will be the first to inform and empower anticholinergic medication users to work with their physician towards a potentially safer medication regimen. We expect our upcoming studies will show that our app and other interventions are effective and practical. If so, future readers of startling headlines about shrinking brains may use our tools as a pathway to safer alternatives.